Black Meadows and the Foundations of Sandy Spring

The next entry of our local history e-newsletter is here! Thank you all so much for being members of the museum and contributing to the preservation of our shared heritage. This month’s exploration is centered around Black Meadows, now known as Riverton. We hope you enjoy this brief glimpse into the past.

Black Meadows: Labor, Land, and the Making of a Community

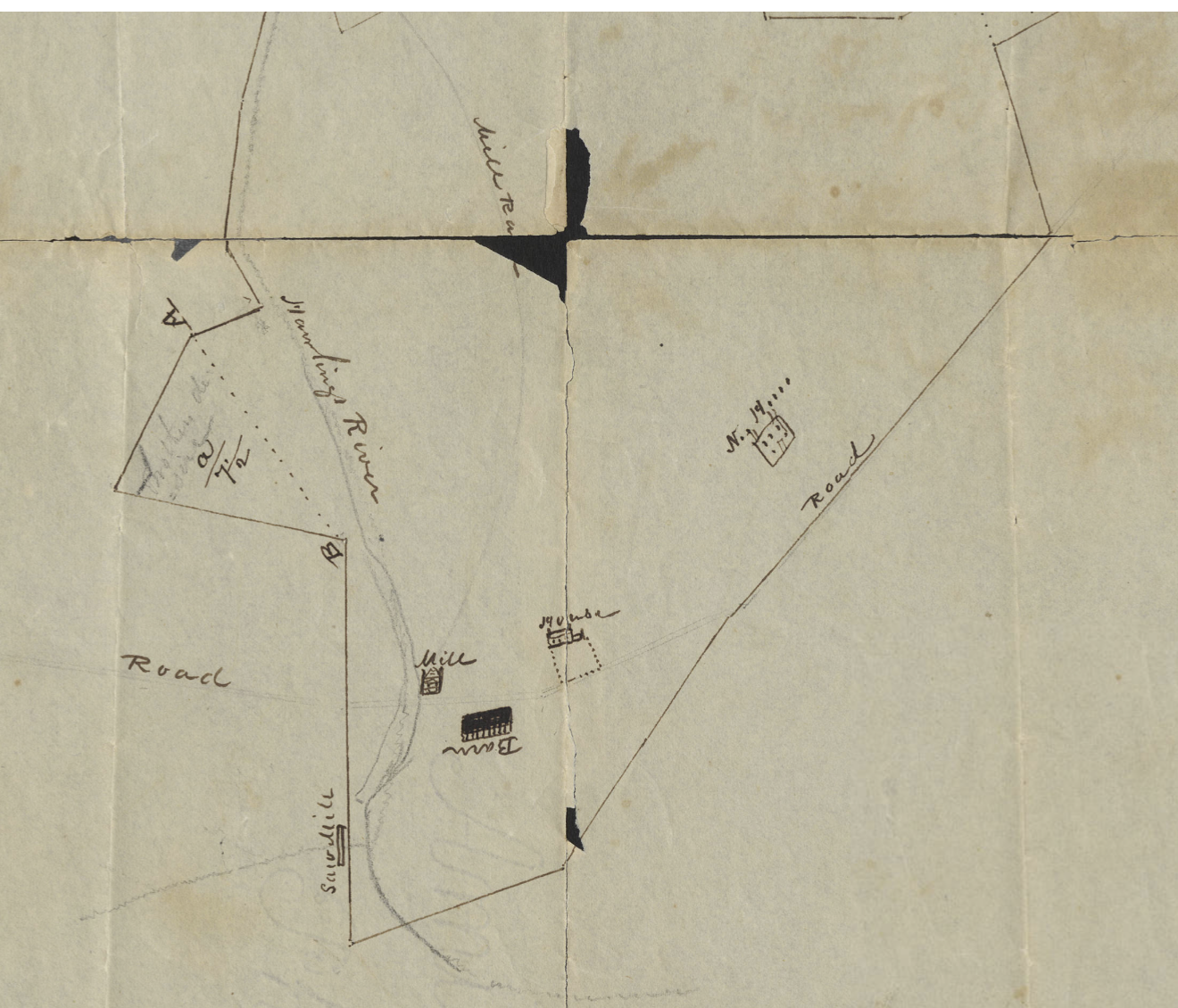

I started my investigation into foregrounding the contributions of the Black community to local landmarks and history with Black Meadows, now known as Riverton, located on Gold Mine Road. Built ca. 1848, it is significant for its association with the Pierce family and its role within the interconnection of the Black and White communities that shaped nineteenth-century Sandy Spring. Rather than hold enslaved individuals, over the course of their approximately sixty-year tenure at Black Meadows, the Peirces employed at least thirty-eight free Black persons. Some were hired on a continuing, year-round basis and others as needed during critical periods in the agricultural cycle. The Peirces likewise provided long-term housing on their farm to at least nine individuals and families.

Black Meadows' free Black laborers worked in exchange for cash, foodstuff, and other forms of barter, including in some cases, housing. Access to employment and housing contributed significantly to broader patterns of Black settlement and community formation. It enabled many free Black individuals and families to migrate to Sandy Spring where they found a relatively safe environment that offered greater opportunity.

Upon their arrival at Black Meadows in 1822, the Peirces first hired brothers and free Black workers John and Samuel Thomas. As farm laborers formerly enslaved by Richard Thomas at Cherry Grove, they brought deep knowledge about day-to-day agricultural practices. Drawing on their experience, they helped guide Westtown-educated Hannah and her former Philadelphia hardware merchant husband Joshua Peirce. The brothers worked year-round, steadily increasing their earnings through their skill and labor. As their wages rose, John used part of his income to rent one of the Peirce's tenant houses and establish a household of his own.

"Post-and-railer" William Bowen contributed to the layout of the Peirce's farm by building fences and drainage trenches to contour the landscape and define fields and livestock areas. His family was among the founders of the Ebenezer kinship community, formerly located in Ashton. Bowen was a landowner and a minister of the church that once formed Ebenezer's spiritual and social core.

Thomas Marriott and Warner Cook both migrated to Sandy Spring bearing Certificates of Freedom testifying to their free status and allowing them to travel unimpeded. Like Jeremiah Bacon, who also migrated here, they secured work and housing at Black Meadows as a foundation for establishing themselves. Warner's wife Louisa took in washing, and their children worked the occasional harvest, while Jeremiah's wife Eliza worked as a domestic at nearby Springdale, a farm carved out of Black Meadow for Peirce's daughter. All eventually purchased small parcels within the community known as Cincinnati and joined the Sharp Street Church, where their children were educated.

Already a member of the Sandy Spring free Black settlement was Levi Hopkins, who at age six was bound into service by his mother Lucy to Joshua Peirce. He lived within the Peirce household for over a decade, eventually establishing his own independent household. His sons later worked at Black Meadow as well, balancing their work life with school attendance.

All of these experiences demonstrate the resilience of free Black individuals and families as they secured housing and employment and built continuity through steady work, shared labor, and the ties of kinship and community. At the same time, they helped ensure the success of Black Meadows farm.