Sandy Spring’s Historic Free Black Community Comes into Clearer Focus

Recent efforts to digitize the museum’s archives have brought long-overlooked records of Sandy Spring’s historic free Black community into clearer focus. Farm ledgers, diaries, and other materials document the skilled labor, resilience, and community-building of Black men and women who lived and worked in and around Sandy Spring—often in close proximity to White Quaker families who owned most of the land.

Many of these individuals had emerged from enslavement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, following gradual manumission by Quaker enslavers. Even after legal freedom, however, Black residents navigated a constrained world shaped by White control over land, wages, and economic opportunity. State laws required White “oversight” of Black religious gatherings, and Quaker landowners both sold land to Black families and employed them as farmhands, domestic workers, and skilled tradespeople.

While free Black labor was essential to the prosperity of Sandy Spring’s farms, compensation was often limited or structured through barter controlled by White employers, making it difficult for Black families to accumulate wealth. Many were able to purchase small plots of land, but these parcels were rarely large enough to sustain farming as a sole livelihood. As a result, Black carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, and other tradespeople frequently supplemented their income by working on White-owned farms—sometimes alongside their children.

Despite these structural barriers, Sandy Spring’s free Black residents built vibrant, enduring communities. Drawing on mutual aid, faith, and shared history, they established fourteen interconnected kinship communities anchored by churches that served as spiritual centers, schools, and social hubs. These institutions were not merely places of worship but foundations of Black self-determination, education, and collective survival.

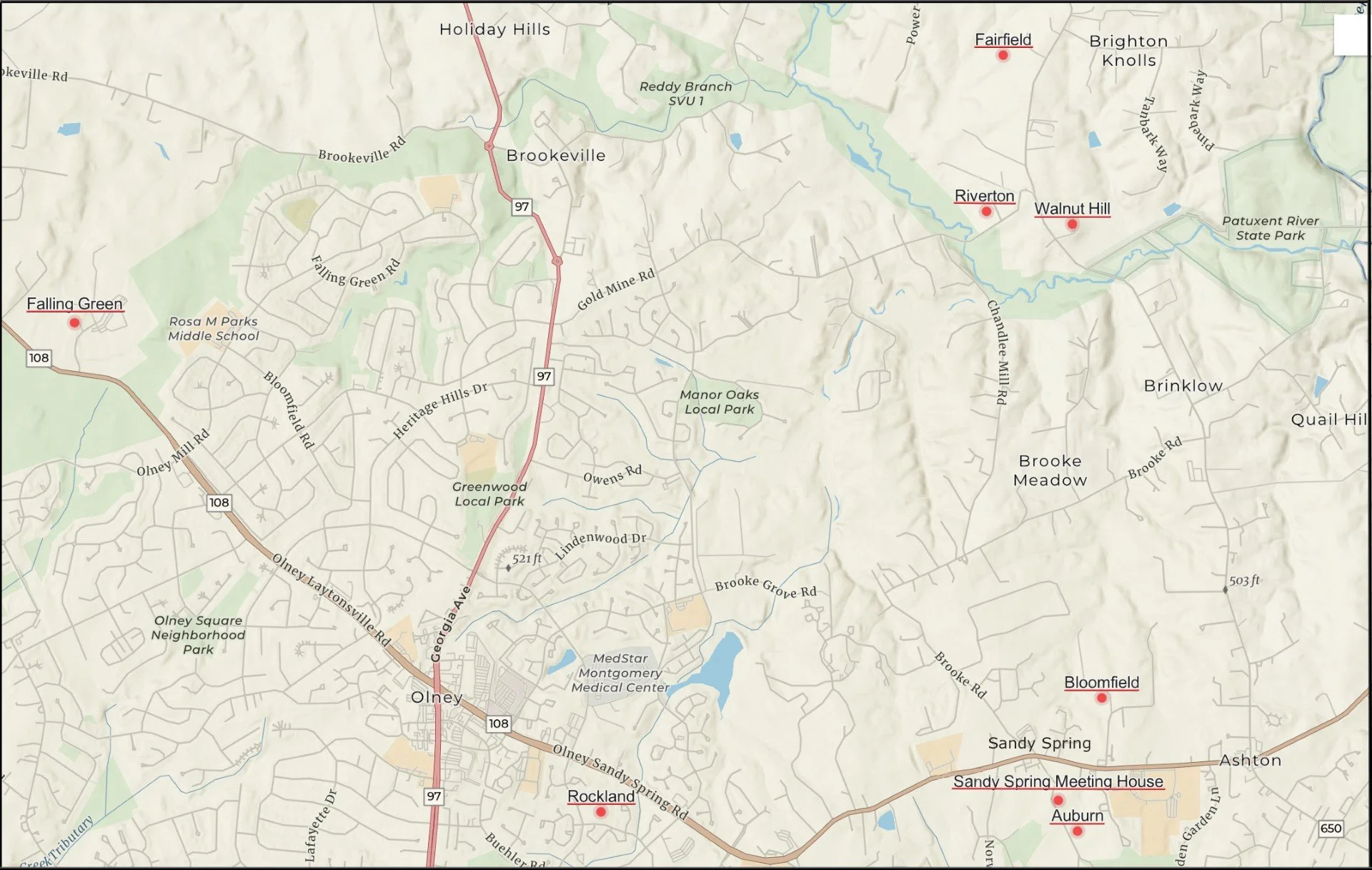

With this history now more visible in the archives, the museum received a grant from the Maryland Historical Trust to update historic site surveys for seven local farmsteads—Auburn, Bloomfield, Fairfield, Falling Green, Riverton, Rockland, and Walnut Hill—as well as the Friends Meeting House. These addendums will document how free Black labor sustained these properties and shaped their development, while also reassessing the architectural history of the farmhouses themselves.

Rather than presenting Sandy Spring’s past primarily through the perspective of Quaker landowners, these updates will illuminate the intertwined histories of Black and White residents—marked by both cooperation and inequity. By centering the experiences and contributions of free Black people, the revised record offers a fuller, more truthful understanding of how Sandy Spring grew into the community it is today.